Lair Of The Clockwork God is a game about getting older: the bewilderment and comedy of being left behind, of becoming less certain and more rigid. It’s the ageing anthem of designer-writers Ben Ward and Dan Marshall, perhaps the first people to star in their own game since Vin Diesel. More precisely, Clockwork God stars polarised caricatures of its lead developers, each with their own way of wrestling mortality. Ben still lives by the self-set rules of ‘90s point-and-click adventures - perambulating levels with one eyebrow raised, and refusing to climb over even the smallest of ledges. Dan, meanwhile, breathlessly chases relevance, ditching the conventions of a dying genre to mantle through the world in the style of popular platformers instead. The pair look like they belong to different games: Ben drawn gangly and aloof like Guybrush Threepwood, Dan shrunk into a squat cube of pixel art. There have been several notable attempts to blend platformer with point-and-click over the years - Ron Gilbert and Tim Schafer have both had a go - but Clockwork God’s great strength is that it doesn’t try to reconcile the two. Ben and Dan might be navigating the same maps, but they’re playing different games; switch to Ben with the tap of a button, and the background objects you sprinted past as Dan become interactive points of interest, the subject of daft dialogue and experimental prods from tools in your inventory.

At one juncture, Ben calls ahead for Dan to read out a paragraph of exposition. “No, Hermione Granger,” Dan responds. Size Five Games throw out brilliant, breezily funny lines like this all the time, as if they’re nothing. Sometimes our protagonists are split up by circumstance, and have to work their way back to each other; often they’re operating on the same planes, Dan transporting Ben by piggyback to areas where he can work his adventuring magic. Fittingly, the puzzles are traditional in the extreme - multi-step Rube Goldberg machines that you must run several times to troubleshoot. The solutions follow a LucasArts form of logic - one that rewards thinking so lateral it’s practically upside-down. But there’s nothing here that’ll tax genre veterans, and if you haven’t pointed or clicked in a while, you won’t find the story held hostage by obscure conundrums.

When you do get stuck, there’s usually the option to switch to Dan and tackle one of his parallel parkour challenges for a bit instead. It helps that Size Five have prior experience in both genres. Clockwork God is not only a quasi-sequel to the studio’s early adventure games - the cult hits Ben There, Dan That! And Time Gentlemen, Please! - but also follows The Swindle, an accomplished stealth platformer. While the camera is ropier than Mario’s, and sound effects don’t always slap the way they would in Rayman, Dan ably hops among his platforming peers.

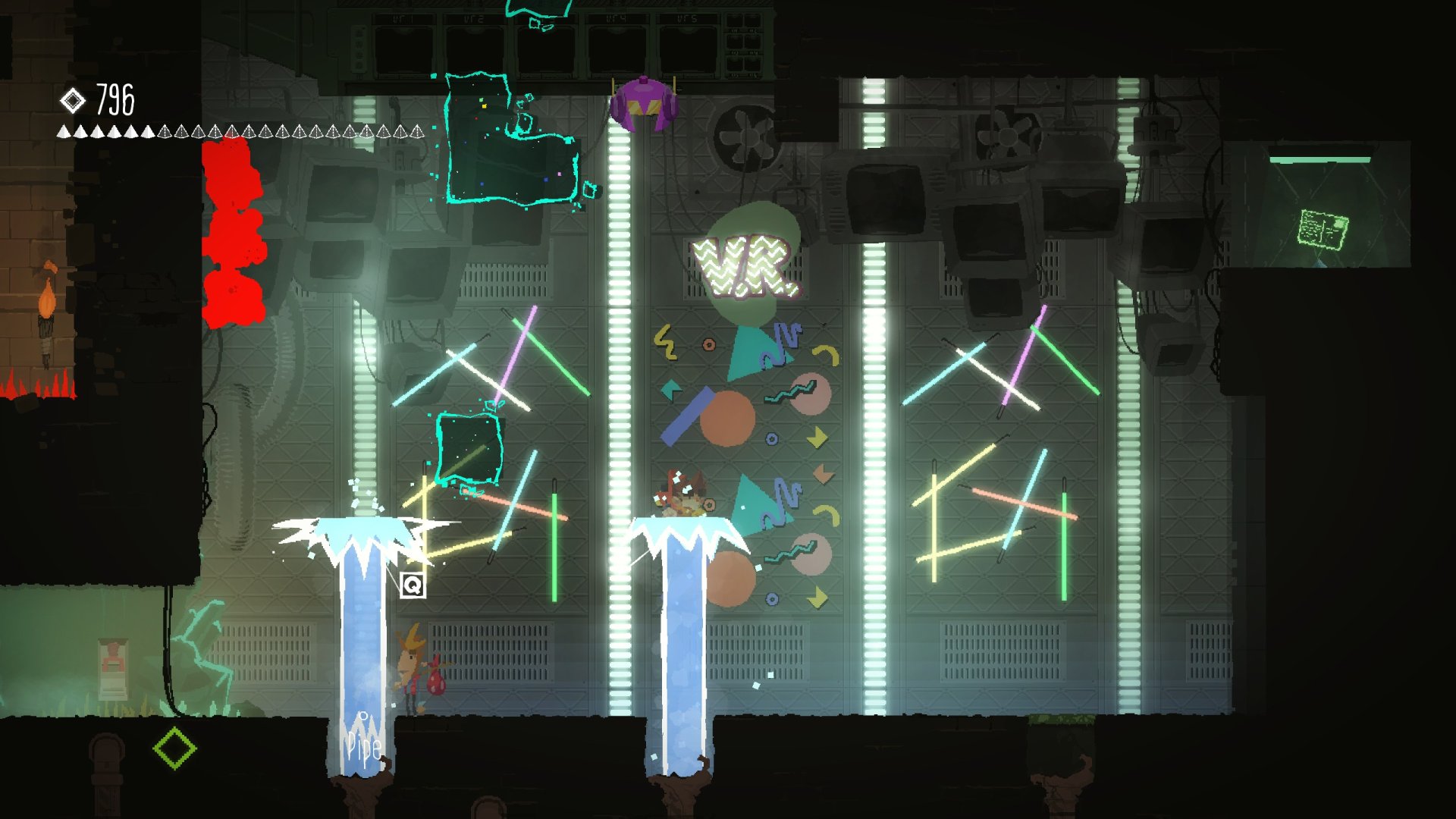

Size Five mainly take aim at - and inspiration from - the acclaimed indie platformers of the past decade or so. Celeste’s abstraction, Super Meat Boy’s frustration, VVVVVV’s loose hold on gravity, Braid’s purple prose - all feature in Dan’s genre crash course, and none escape Ben’s withering quips. To make truly great parody, especially the interactive kind, you have to love the stuff you’re ripping to shreds, and Size Five clearly adore every part of its platforming collage.

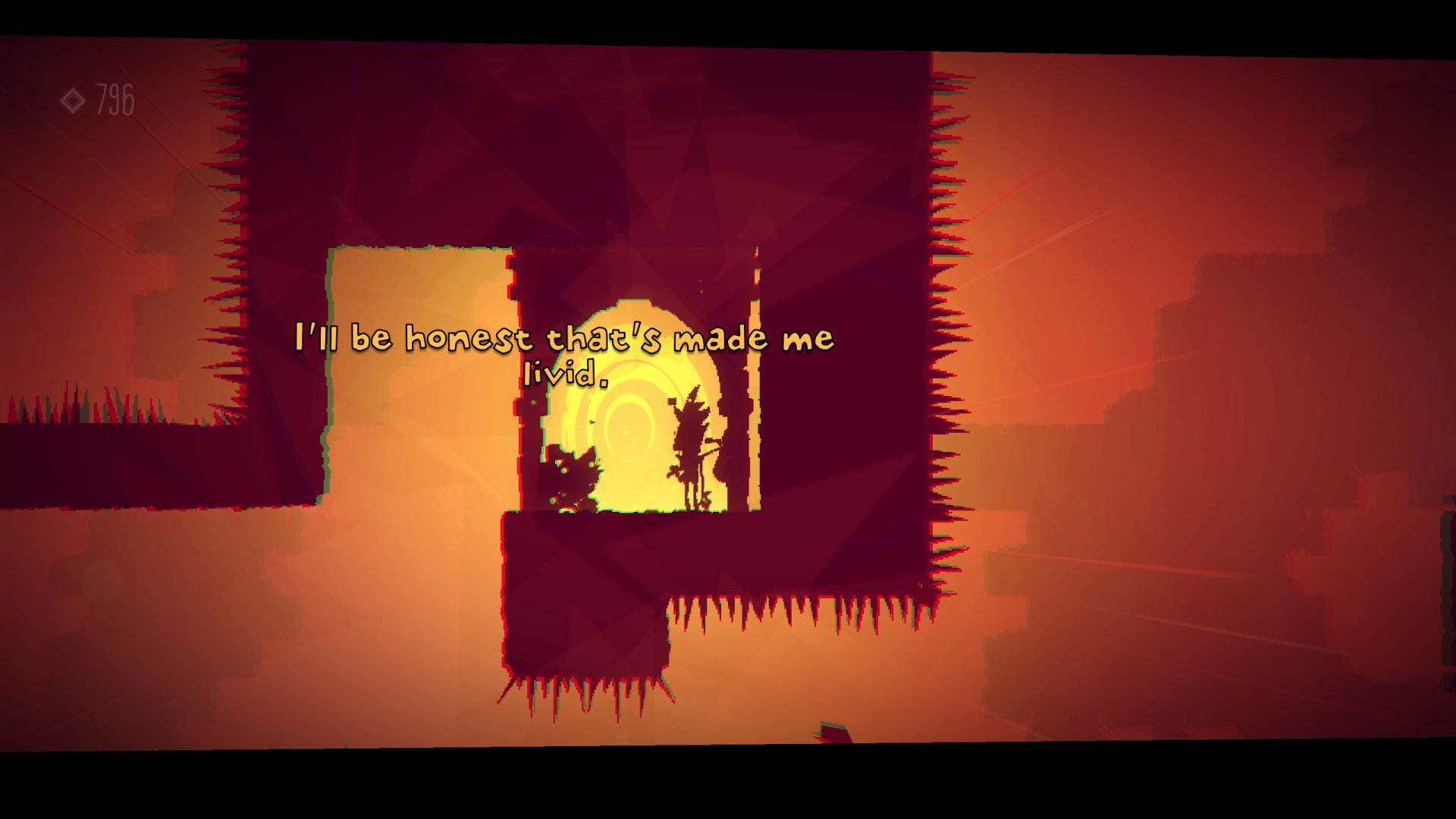

Normally, when a game knocks incessantly against the fourth wall, it’s cause for concern - a sign that even the developers don’t really believe in the world they’ve built. But Clockwork God has its own story to tell. Earth’s firewall against world-ending disaster is on the blink, and to get it back online, Dan and Ben must teach the hardware to care about humanity again. That means running themselves through a series of simulations designed to elicit core emotions: joy, fear, anger, and so on. As they do so, the sentient computer at the story’s centre grows in complexity. Its new emotions factor into conversation, and the machine ages before their eyes. It begins to harbour insecurities, nurse resentments, and develop a promising sideline in passive aggression. Like Dan and Ben, it struggles to embrace the greyer aspects of the human experience.

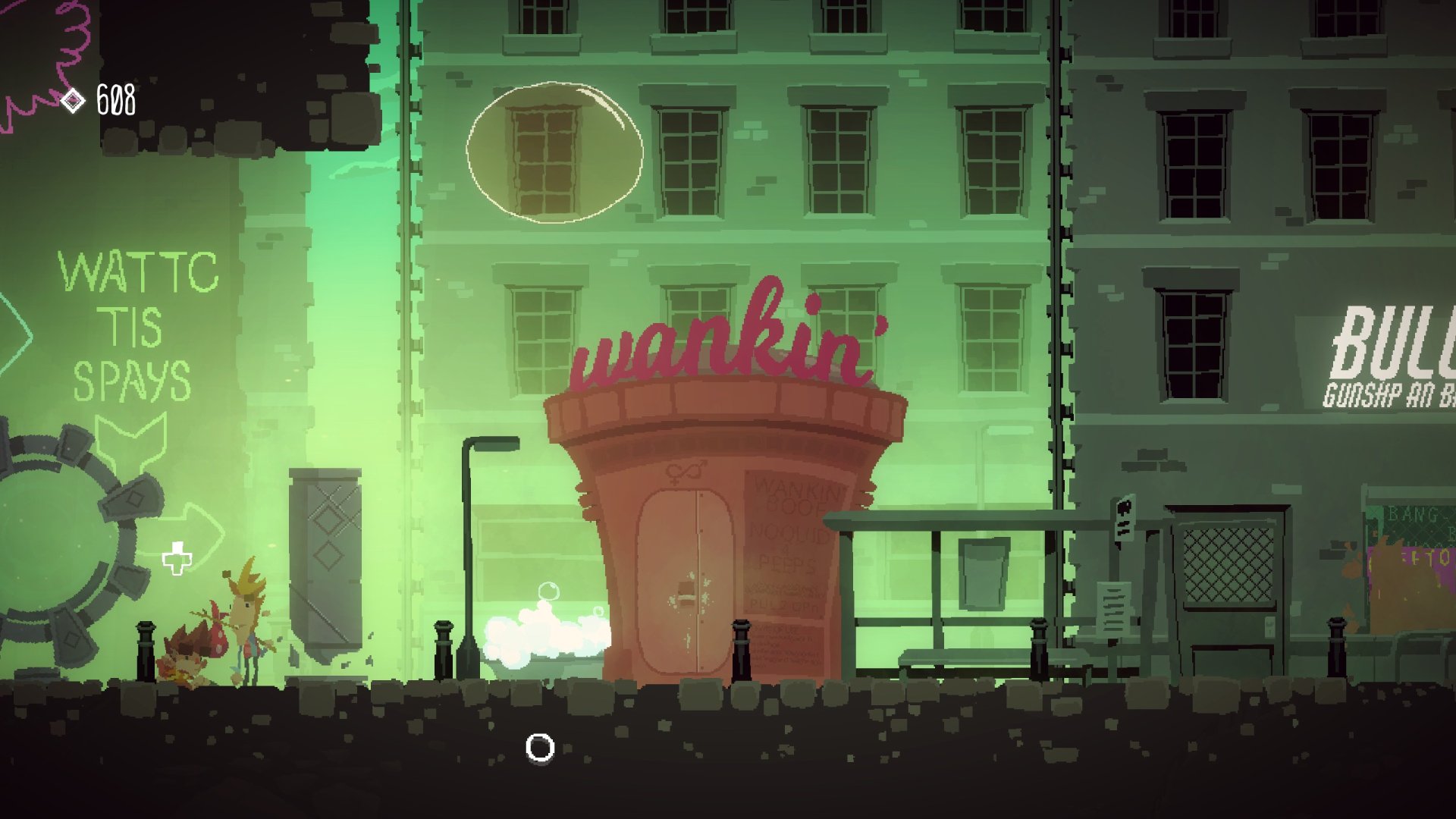

Humour is subjective, but Clockwork God’s grasp on comedy seems pretty inarguable. It is a stress test for the rib cage. It equals Schafer in terms of sass and sharp observation, and grounds its big ideas in a British sensibility that regularly defaults to knob jokes and GCSE references. There are a couple of jokes in there with set-ups so slow-burn and subtle that, when the punchlines dropped, I couldn’t laugh for gasping. At times, I felt as if I was playing a fictional game Nate might come up with on a slow Monday. Clockwork God has a touch of the Garfield Kart Furious Racings about it.

Your mileage may vary - or, to put it more concisely, your age may vary. It might be that I connect with Clockwork God so strongly because, a week away from turning 30, I’m entering the liminal space it concerns: doing the work to keep myself socially educated, still participating in youth culture, yet accepting that it will never again be made for me. I can choose to be Ben, stubbornly flying the flag for the old ways. Or Dan, desperately tripping after a place in society I can never again occupy. Whenever Clockwork God threatens poignancy, Ward and Marshall can’t help but lob in something puerile, like a grenade full of piss. But their real friendship, and years of collaboration, can’t help but result in genuine weight. Somewhere in the mix, these two best mates have found the self-awareness that leads to acceptance. Clockwork God celebrates the tension between old and new, and finds profound comedy in the juxtaposition. It’s Size Five’s masterpiece. Nice historhythm, gramps.